Andrea Lucky is an entomologist at the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Florida. She studies insects and her specialty is ant evolution. In January 2021, Andrea arrived in the Czech Republic to explore the dynamics and impact of insect education in Czech Republic, “the world's most entomologically-literate nation." Familiar with iconic children’s stories of the beloved cartoon character, "Ferda Mravenec," (meaning Ferda the Ant), Andrea is curious about the impact of insect-rich Czech children’s literature on generations of children, who grow up following the stories of Ferda and his insect compatriots in an anthropomorphized insect empire. Together with her colleagues at the Faculty of Science of Charles University in Prague, Andrea is exploring the noted Czech passion for insects during her 8-month Fulbright research grant.

Did you know that worker bees and ants are all female? That, despite their common names, ladybugs and fireflies are both beetles? Would you be able to distinguish a stag beetle from a scarab? If you answered yes to some of these questions, you would be in excellent company in the Czech Republic, where common knowledge about insects is, well… common. Most Czechs know a lot about the insects around them and, considering the small size of this nation, Czechs are disproportionately well represented among professional entomologists. Ask any Czech if they ever collected insects or raised them as pets and you may be surprised at the gleam in their eyes as they recall childhood summers spent chasing butterflies with a net…

I came to Czechia as a Fulbright scholar to look more deeply into the famed “Entomological Literacy” of Czechs. As a US entomologist who studies not just the insects (my specialty is ant evolution), but also the mechanics of science education, I wanted to look outside of the US to understand how students learn the skills of my profession. Because entomologists impact so many realms of society, spanning applied fields such as food production, pest control, biodiversity conservation, public health, as well as basic scientific research in the realm of evolution and genetics, it is essential that our university-level curriculum is international in perspective.

One of my driving questions was whether Czechs really are extraordinarily knowledgeable about insects. Informally, Czechia, Japan, Germany, and Britain are among the nations considered to have the strongest entomological traditions. One piece of evidence supporting Czechia’s top standing includes the pointed distinction of producing most of the world’s insect pins.

Image 2: An astounding variety of insect pins are produces in Czechia and sold around the world. (Over two dozens of boxes with insect pins, some of them labeled as "Bohemia insect pins.")

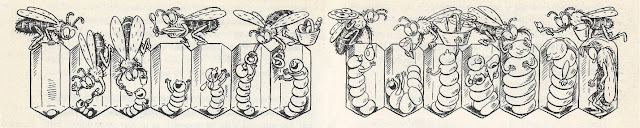

Another, more widely appreciated hint about the cultural importance of insects in Czech culture is in literature, which abounds with insects in remarkable biological detail. Consider an illustrated inset in an adventure book for young readers that perfectly details the life cycle of a honeybee: from egg to larvae to pupae, “nurse bees” tend to each growing bee in its own beeswax cell. As in a real hive, babies “beg” to be fed, though here they cry and cheer with cartoonish glee. Hilariously, the young are fed soup, pretzels, sugar, and cakes rather than the fermented pollen and nectar mixture known as bee bread. A worker bringing mortar in bucket seals up the cells of the fully-grown larvae, and in the last cell we see an adult bee, fully metamorphosed and almost ready to emerge. A biology lesson in a single cartoon!

Image 3: The illustrated life cycle of the honeybee, with characteristic Czech humor, by Ondrej Sekora. (A black-and-white illustration of insect life cycle from an egg to a honeybee in 14 stages.)

Insect characters are universally anthropomorphized, but these books abound with precise biological detail, illustrating species-specific behavior and ecology, always with a dose of adventure and humor. Ask any Czech to name the most famous insect they know. The answer, inevitably, is either the heroic Ferda Mravenec (Ferdinand the Ant) or his compatriot in field and forest adventures, the bumbling and boastful Brouk Pytlik, (Bags the Beetle). In the many volumes of stories by Ondrej Sekora, these two characters make their way through every variety of Czech habitat where they have memorable encounters with the distinctive insects in each. Interested in the architecture of an anthill? Curious about the critters making pebbled cases on the riverbottom? Just follow Ferda. Lest this sound pedantic, be assured that fantasy, sport, and practical jokes rule these pages, just in a flurry of wings and jointed legs.

Image 5: Andrea Lucky (center), with Charles University colleagues Petr Novotny (left) and Vanda Janstova (right), with an example of several questions from the insect knowledge survey. (Three people pose for a group picture. Next to the photo are insect knowledge survey samples with insect images.)

Beyond simply answering the question of just how much Czechs know about insects, I wanted to know how a culture becomes insect-savvy. My goal was to go beyond formal curriculum to also explore the influence of history, family, literature, and art in shaping cultural attitudes, so I could bring useful lessons back my home department at the University of Florida as well as to informal science education settings. COVID-19 presented me with some unexpected challenges to studying culture directly. Whereas my academic colleagues and I quickly adapted to meeting online when in-person office meetings were not possible, it was harder to find ways to interact with students, schools, and camps online.

I managed a few socially distanced field trips with university students and colleagues, but much less than I would have in a non-COVID year.

Image 6: Left: Insect collecting just outside of Prague, in Radotin, with Charles University entomology undergraduate students (Andrea Lucky on Right). A meet-and-greet coffee break with Entomology instructors and students at the end of an online-only entomology course. (Two group pictures. One features four insect collectors on a grass field. The other one features six young people and Andrea enjoying tea and coffee outside.)

Image 7: Top Left: Kids playing on an insect themed playground – note the wooden ant at the center of the climbing structure! Top Right: kids explore a wood-ant mound in a forest near Prague. Bottom Left and right: Happy kids enjoying the local insect diversity. (Four photos of children playing. Top Left: five children play in a wooden, insect themed playground, a wooden ant at the center of a wooden climbing structure. Top Right: kids explore a wood-ant mound in a forest. Bottom Left: a girl watches a butterfly sitting on a flower. Top Left: a boy holds a beetle in his right hand.)

When I return to the US, I’ll be incorporating much of what I learned here into my educational research and teaching, as well as into my educational outreach programs. Clearly, a positive cultural attitude can be cultivated through arts and culture. In addition to continuing the collaborative research my colleagues and I began this year, perhaps the next class I’ll teach will be a global survey of ants in literature… would you take a class called Formic Fiction?

I came to Czechia as a Fulbright scholar to look more deeply into the famed “Entomological Literacy” of Czechs. As a US entomologist who studies not just the insects (my specialty is ant evolution), but also the mechanics of science education, I wanted to look outside of the US to understand how students learn the skills of my profession. Because entomologists impact so many realms of society, spanning applied fields such as food production, pest control, biodiversity conservation, public health, as well as basic scientific research in the realm of evolution and genetics, it is essential that our university-level curriculum is international in perspective.

One of my driving questions was whether Czechs really are extraordinarily knowledgeable about insects. Informally, Czechia, Japan, Germany, and Britain are among the nations considered to have the strongest entomological traditions. One piece of evidence supporting Czechia’s top standing includes the pointed distinction of producing most of the world’s insect pins.

Image 4: Treasured books from colleagues bookshelves include Ondrej Sekora’s insect-themed children’s stories and an 1896 natural history tome describing the fauna of central Europe, Maly Brehm, by Bohuslav Zaborsky. The illustration depicts a wood-ant mound. (Three different book covers, two with colorful insect world illustrations and one with a black-and-white wood-ant mound.)

To return the research questions that brought me here, I wanted to test the theory that Czechs are distinctive in their passion for insects. No formal metric existed for measuring and comparing entomology knowledge, so I developed a formal survey to quantify knowledge and attitudes about insects. My partners in this endeavor were my Czech colleagues in Charles University’s Department of Teaching and Didactics of Biology, the nation’s experts in biology education. Our collaboration was a true intercultural partnership, combining their expertise in educational assessment and my knowledge of the subject matter. We worked closely together to construct a survey that worked equally well in both the US and Czechia culture. Keeping in mind that this survey will be used for future intercultural comparisons, we established a framework for translation to other languages. After initial pilot testing, we disseminated our survey as an online questionnaire to 1st year university students across Czechia and in the USA, receiving more than one thousand responses. We are still analyzing the data, but now I have an answer to at least two questions: 1) college-bound Czech students know significantly more about insects than their US counterparts and 2) there is a positive relationship between attitude towards insects and knowledge about them. This leads to a chicken-and-egg question: does a positive attitude lead to better knowledge or does knowing more about insects make people feel more positive about them? I’ll be pursuing that question next!

Beyond simply answering the question of just how much Czechs know about insects, I wanted to know how a culture becomes insect-savvy. My goal was to go beyond formal curriculum to also explore the influence of history, family, literature, and art in shaping cultural attitudes, so I could bring useful lessons back my home department at the University of Florida as well as to informal science education settings. COVID-19 presented me with some unexpected challenges to studying culture directly. Whereas my academic colleagues and I quickly adapted to meeting online when in-person office meetings were not possible, it was harder to find ways to interact with students, schools, and camps online.

I managed a few socially distanced field trips with university students and colleagues, but much less than I would have in a non-COVID year.

I did get to know my colleagues' kids quite well, though, as school was conducted online for much of the school year. As each of us had multiple elementary school-age children at home, it was typical for our meetings to be joined by kids popping in to say hello or parents stepping away for a moment to help with homework. This family-inclusive atmosphere extended to weekend excursions with my colleagues. Talking with kids about insects may have taught me the most of all about how Czechs come to know about and care about nature! I saw firsthand how common it is for children to spend time in nature with their parents, and how nature appreciation is encouraged from the earliest age.